Dhunning - Indigenous Impact

If I can change one life …

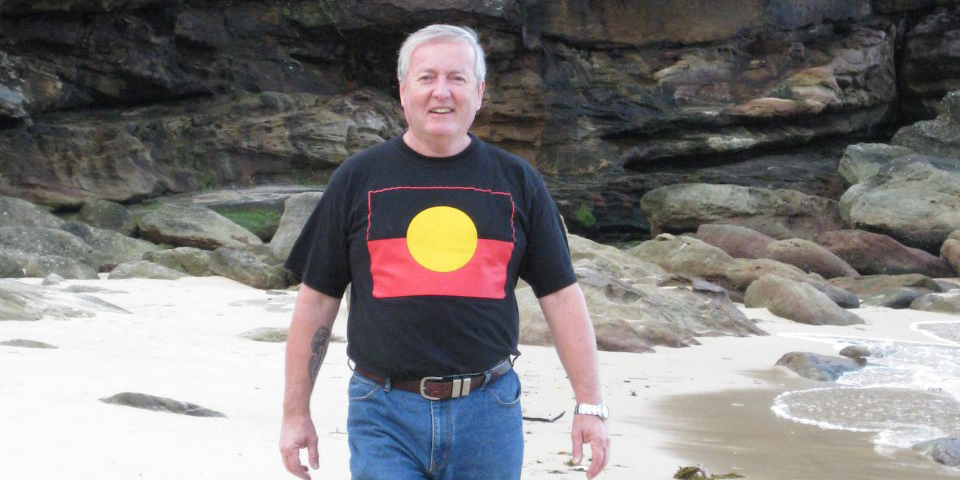

Dennis Foley has led a life less ordinary.

Identifying as Koori, Dennis’ matrilineal connection is Gai-mariagal of the northern suburbs of Sydney, including the Cammeraigal clan. His father is a descendant of the Capertee/Turon River people, of the Wiradjuri.

And his story began in the heart of a large and loving family – until he was stolen from them.

That was a catalyst for the anger that once drove him, but which he has – in large part – transmuted into a passion for knowledge-driven change.

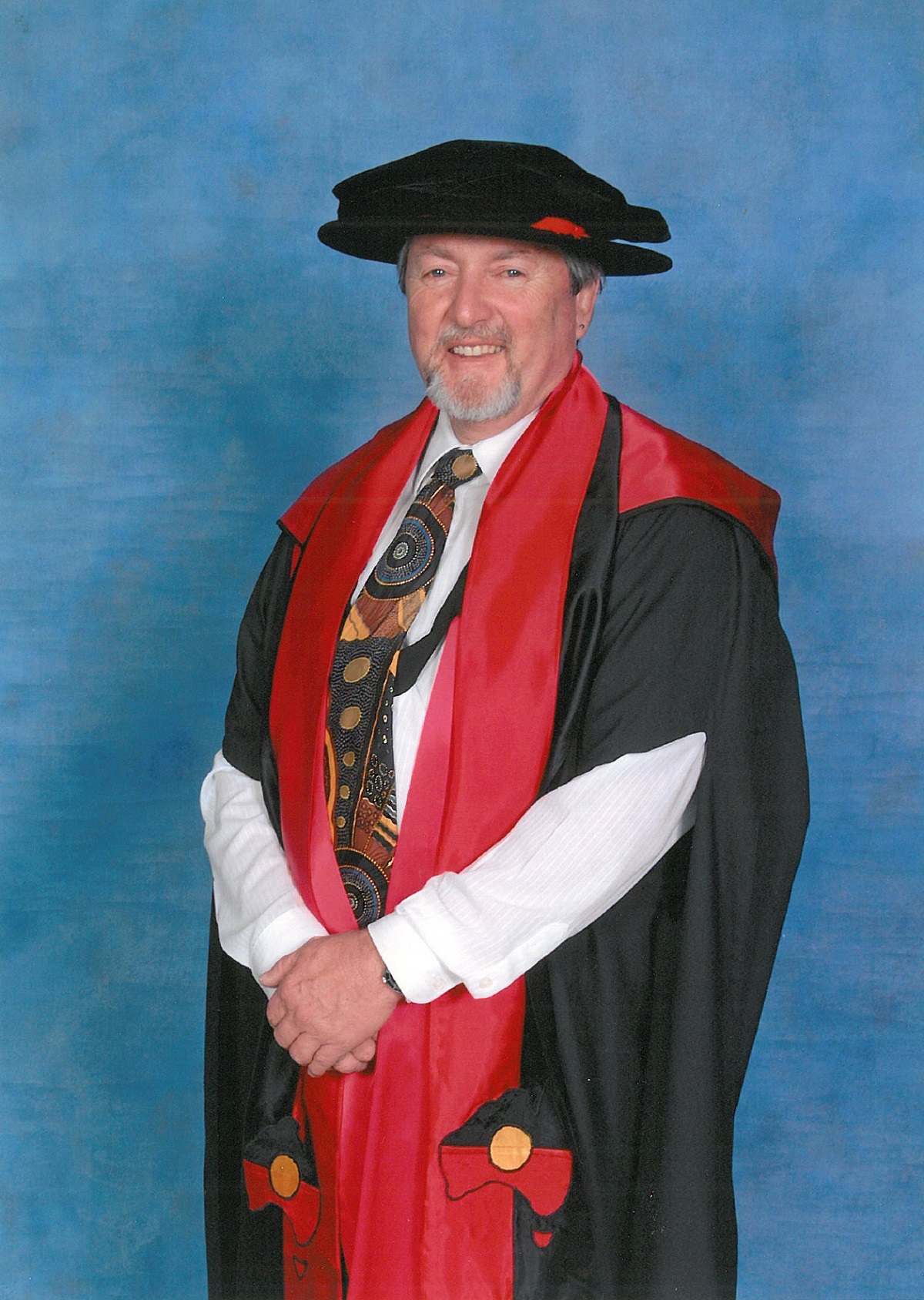

“I guess you could say the fierce anger of my youth has been distilled into educational pedagogy,” says the Professor of Entrepreneurship with the Faculty of Business, Government and Law at the University of Canberra.

“It took me a long time to figure out that anger wasn’t going to get me anywhere. Especially in the last five or six years, as my grandchildren have grown older, I have asked myself – do they want to see an angry old man, or a wise old man?”

Dennis has a rich, diverse body of work across disciplines ranging from Indigenous literature to history to education, business management and leadership. He is a Fulbright Scholar and double Endeavour Fellow, sits on several national and international research boards and has received a series of competitive research grants, including five Australian Research Council grants, co-chief investigator on a National Health and Medical Research Grant and two Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Grants.

Dennis’ principal speciality – and closest to his heart – is in the field of Indigenous enterprise, entrepreneurship and Indigenous pedagogies-epistemology (the philosophical study of knowledge and the imparting of such). This is reflected in the three postdoctoral fellowships that he undertook at the Australian National University within anthropology, economics, and law – all of which had an Indigenous entrepreneurship focus.

His focus is on Indigenous economic development and engagement in the modern economy. Dennis’ research in this field has also seen him work with First Nations people in Canada, Maori in Aotearoa and with the Aboriginal people of Ireland.

And yet, Dennis still refers to himself as an ‘accidental academic’.

“I only went to university when I was 40,” he says. “I liked school, and I really enjoyed sports – but my teachers used to tell me I was just a dumb black lad.

“When I got the chance to go to uni, that was when I discovered how powerful education really is – it lets you know that you are as good as anybody else.”

Dennis says that his many amazing students have been a constant source of inspiration.

“I remember one young boy, who had never been to school, could barely speak English, and was living on the streets at 14 – he graduated from Melbourne University and today he is a teacher. A phenomenal one, at that.”

“Students like that, stories like that, are a testament to the power of education, belief and support – and why I keep doing what I do. I know that if I can change the life of one kid, they will go on to change the lives of others.”

The first 10 years of Dennis’ own life were spent on Sydney’s northern beaches, where he lived with his maternal grandmother.

“When she was diagnosed with cancer, I went to live with my mother,” he says.

But just a few short weeks after that, he was taken from her by the Welfare department.

“My dad had been in the hospital with cancer, and so we were a little behind on our rent,” Dennis says. “That’s why a government official came to our place – and when he saw me, a little fair-skinned boy … well, they came and grabbed me at school soon after.”

Dennis was sent to live with foster parents in Bathurst, who treated him like a veritable slave. Eighteen months later, the abysmal treatment caused him to run away.

At just 11, Dennis found himself living on the streets of King’s Cross with a cousin.

“Just before high school began, a social worker found us living on the streets and sent me back to live with my older sister,” he says. “Not everyone was so lucky – I had 21 girl cousins, all gone without a trace.”

“The destruction of our families has been phenomenal. We had a huge, loving family, and by 1966, it was destroyed. Decimated by the children being taken away, and after a while, the parents would stop showing up to gatherings.”

Dennis nonetheless counts himself lucky that he could return to his family and his culture.

“My mother had two strong brothers, initiated men. My grandmother and her sisters took me through my own training – which is a lifelong experience – so I had a constant connection to the elders,” he says.

“The intergenerational violence and trauma inflicted on us as Indigenous peoples causes a lot of anger. I was able to maintain that connection with my elders, but what of a young child growing up in the suburbs with little to none of that connection – imagine the disconnect, where would they get their knowledge from?”

At 30, Dennis moved to Queensland, striking up a relationship with the Stradbroke Island community, and they invited him to undertake ceremony.

“Ceremony [Initiation] is intensive – it’s like doing a PhD in a few months! It also meant the world to me.”

There is a lack of understanding of the breadth and depth of Aboriginal culture that needs to be addressed, in order to handle the thorny issue of stereotyping, Dennis feels.

Aboriginal culture is not homogenous, and the oversimplification and conflation of cultural diversity is just another product of colonialism.

“Many people think that ‘Aboriginal culture’ is just one thing, that we are all the same,” Dennis says. “We are not. It’s like looking down at the map of Europe and understanding that one continent has all these different countries – Indigenous Australians have 400 major languages, 1,100 dialects.”

“Understanding this is a first step to breaking down stereotypes.”

Dennis’ life has been hallmarked by a myriad of achievements, but he doesn’t have to think twice about what – or rather, who – he is proudest of.

“I’m proudest of my daughter,” he says, simply. “She struggled in high school, but then she got into Nursing at Griffith University – and she was the only one from her high school who finished the course.

“She is a classic example of what can happen when you believe in and support an Aboriginal child.”

“As an academic, this is how I see it: grants are wonderful and important, but when you see a student who is struggling and you can reach out and help instil confidence in them … and then you go on to watch them graduate … that is the moment that matters.

“It is the moment in which the shackles of oppression and poverty are slowly broken away. Education can provide self-determination, for when you are educated you have a better chance of employment, and with employment comes financial independence – and that is self-determination.”

Words by Suzanne Lazaroo, photos: supplied.